TDD/React/Redux/Enzyme: Thoughts on Testing the Dispatch of Action Creators and/or Prototype Methods for a React Component Connected to a Redux State

One of my recent projects is Birch, a web app to search for books. It was built primarily using React, it has a Redux-managed state, and its search functionality is powered by the Google Books API.

A major goal of mine while working on this project was to write a suite of tests for the app, taking a unit-testing approach. I made many mistakes along the way, but I learned a ton. One of the biggest practical and philosophical issues I wrestled with was how to test the functionality a React container component that is connected to a Redux state via #mapStateToProps and #mapDispatchToProps.

In particular, imagine that the component has:

(a) props that dispatch action creators thanks to #mapDispatchToProps, and

(b) prototype methods that handle calling these props.

How do you test these situations? And if you’re using Enzyme for testing, when do you use #shallow instead of #mount?

There are so many great articles out there on testing with Redux (see, for example, here, here, and here). But I often found myself wishing that I had a super simple example to stare at. I hope this post serves that purpose for others who might be in the same boat. It assumes the reader has a bare-bones familiarity with (1) Enzyme to test React components, in conjunction with the Chai assertion library, (2) redux-mock-store for testing whether actions are being passed successfully to the Redux store, and (3) Sinon for using function spies and stubs.

Also, please note that this post does not discuss other functionality that you may want to test. This post only explores (a) and (b) above and suggests one way of getting the tests to work.

The complete code for the examples below can be found here.

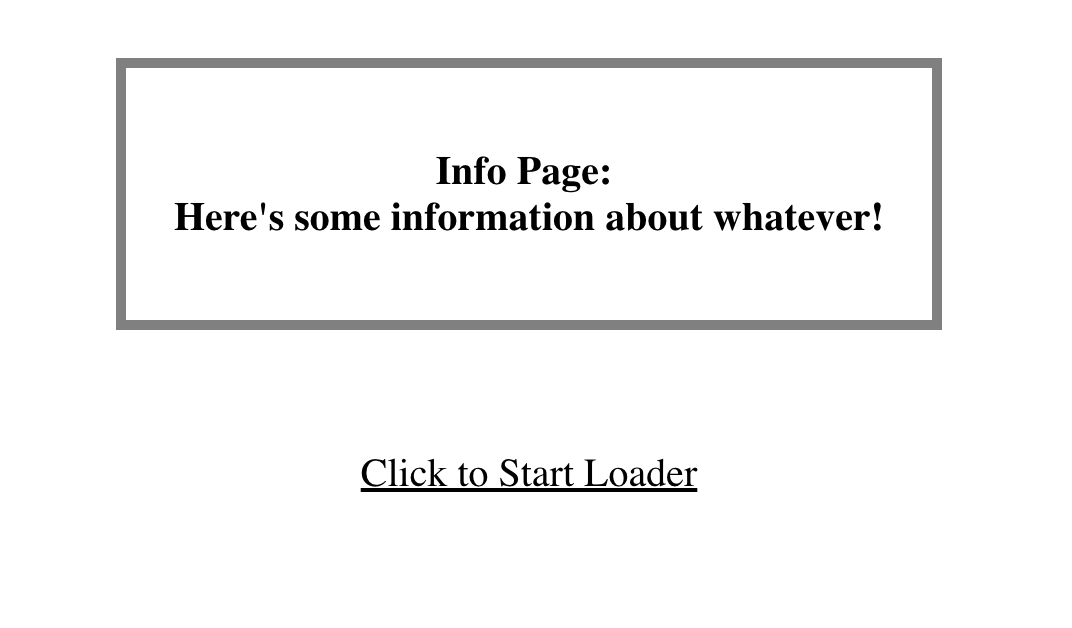

Let’s start with our super simple example. Imagine we have an <App> component does only two things: it displays a Loader, or it displays an Info Page. Which one is displayed depends on our state, specifically whether state.loaderRunning is true or false. To toggle between the two displays, there two links: “Click to Start Loader” or “Click to Stop Loader and See Info Page,” which change state.loaderRunning to true or false, respectively.

Here’s our reducer, showing our super simple state:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

// rootReducer.js

function rootReducer(state = {loaderRunning: false}, action) {

switch(action.type) {

case 'START_LOADER':

return Object.assign({}, state, {loaderRunning: true})

case 'STOP_LOADER':

return Object.assign({}, state, {loaderRunning: false})

default:

return state

}

}

export default rootReducer

Here are our action creators, which we dispatch to the reducer to change the state:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// actionCreators.js

export function startLoader() {

return {type: 'START_LOADER'}

}

export function stopLoader() {

return {type: 'STOP_LOADER'}

}

And here’s our <App> component. Please note that we’re importing a <Loader> component and an <InfoPage> component to render along with <App>, but their code is omitted for the sake of brevity. We’ll have to use our imaginations instead.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

// App.js

import React, { Component } from 'react'

import { connect } from 'react-redux'

import { startLoader, stopLoader } from './actionCreators'

import Loader from './components_presentational/Loader'

import InfoPage from './components_presentational/InfoPage'

class App extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.handleLoaderStart = this.handleLoaderStart.bind(this)

this.handleLoaderStop = this.handleLoaderStop.bind(this)

}

handleLoaderStart(event) {

event.preventDefault()

this.props.dispatchStartLoader()

}

handleLoaderStop(event) {

event.preventDefault()

this.props.dispatchStopLoader()

}

render() {

if (this.props.loaderRunning) {

return (

<div>

<Loader />

<a href="" onClick={this.handleLoaderStop}> Click to Stop Loader and See Info Page </a>

</div>

)

} else if (!this.props.loaderRunning) {

return (

<div>

<InfoPage />

<a href="" onClick={this.handleLoaderStart}> Click to Start Loader </a>

</div>

)

}

}

}

const mapStateToProps = (state) => {

return {

loaderRunning: state.loaderRunning

}

}

const mapDispatchToProps = (dispatch) => {

return {

dispatchStartLoader: () => dispatch(startLoader()),

dispatchStopLoader: () => dispatch(stopLoader())

}

}

export default connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(App)

And of course, because <App> is connected to the Redux store via #mapStateToProps and #mapDispatchToProps, <App> has to be wrapped in a Redux <Provider>. So here’s what our index.js looks like to handle this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

// index.js

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

import './index.css'

import { createStore } from 'redux'

import { Provider } from 'react-redux'

import App from './App'

import * as serviceWorker from './serviceWorker'

import rootReducer from './rootReducer'

const store = createStore(rootReducer, window.__REDUX_DEVTOOLS_EXTENSION__ && window.__REDUX_DEVTOOLS_EXTENSION__())

ReactDOM.render(

<Provider store={store}>

<App />

</Provider>,

document.getElementById('root'))

serviceWorker.unregister()

(On line 13 above, the second, complicated argument for #createStore, after rootReducer, allows us access to the fantastic Redux DevTools browser extension.)

Now, regarding tests for <App>, here are a few things we can think about:

(a) How can we test that #this.props.dispatchStartLoader and #this.props.dispatchStopLoader actually dispatch the #startLoader and #stopLoader action creators to our Redux store (respectively)?

(b) How can we test that the prototype methods #handleLoaderStart and #handleLoaderStop call #this.props.dispatchStartLoader and #this.props.dispatchStopLoader (respectively)?

If we can nail down tests for these, we have a good chunk of <App>’s functionality covered. Let’s tackle (a) first.

Part 1: How can we test that #this.props.dispatchStartLoader and #this.props.dispatchStopLoader actually dispatch the #startLoader and #stopLoader action creators to our Redux store (respectively)?

Here’s what I learned:

-

Because we are testing functions connected to the Redux store (via

#mapDispatchToProps), our tests need to render a component that is connected to a store. To accomplish this, we need to rely on Enzyme’s full rendering capabilities via#mount, instead of shallow rendering with Enzyme’s#shallowmethod. With<App>as it is above, particular with us exporting a Redux-connected component (App.js, line 61), our tests will throw an error if we try to#shallowrender<App>. Using#mountin this case seems to be a necessary evil, as many advocate favoring#shallowwhenever you can (see here, for example). -

Unfortunately, using

#mountto render<App>is not enough by itself. We need to wrap<App>in a<Provider>with a store passed in as a prop. For example, if we try to render<App>this way in our Enzyme test…

const wrapper = mount(<App />)

…we’ll get an error with this helpful message:

Invariant Violation: Could not find "store" in the context of "Connect(App)".

Either wrap the root component in a <Provider>, or pass a custom React context

provider to <Provider> and the corresponding React context consumer to

Connect(App) in connect options.

The Redux folks’ helpful discussion here explains what is going on behind the error. But to keep thing simple for now, let’s take the error message at its face and wrap <App> in a <Provider>, just as we did in index.js above. For this wrapping to be successful, though, we’ll need to pass the <Provider> wrapper a store prop. And because we want to test which action creators are dispatched to the store, we’ll need a handy tool like redux-mock-store to mock a store for us. By mocking a store with redux-mock-store and calling #getActions on the mock store object, we can see which actions (or action creators) were dispatched to the store.

With this in mind, we have enough to begin to flush out our #mount of <App>. Here’s what our file might start look like. This does not results in any errors being thrown:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

// App.test.js

import React from 'react'

import { Provider } from 'react-redux'

import { expect } from 'chai'

import configureMockStore from 'redux-mock-store'

import Enzyme, { shallow, mount } from 'enzyme'

import Adapter from 'enzyme-adapter-react-16'

Enzyme.configure({ adapter: new Adapter() })

import App from '../App'

import { startLoader, stopLoader } from '../actionCreators'

const mockStore = configureMockStore()

const mockState = {}

describe("<App />", function() {

describe("#this.props.dispatchStartLoader", function() {

it("dispatches the #startLoader action creator to the Redux store", function() {

// incomplete test; just illustrating set up for wrapper

let store = mockStore(mockState)

const wrapper = mount(

<Provider store={store}>

<App />

</ Provider>

)

})

})

})

But, we still need to do one more thing before we can write a test…

- Because we have wrapped

<App>in<Provider>, ourwrapperobject created by#mountis not actually what we want to test.<App>is now a child buried in thewrapperobject. The punchline is to get at what we want, ourApp.jsfile has to export both an<App>connected to the Redux store and an<App>that is not connected to the Redux store. The former we wrap in<Provider>, and the latter we isolate with Enzyme’s#findand#instancemethods in order to test<App>’s dispatching props functions.

I know, this sounds crazy and thorny. It took me a while to understand and learn to work with it. I’m the type of person who needs to see something in action to understand it, so let’s see if we can do something along those lines.

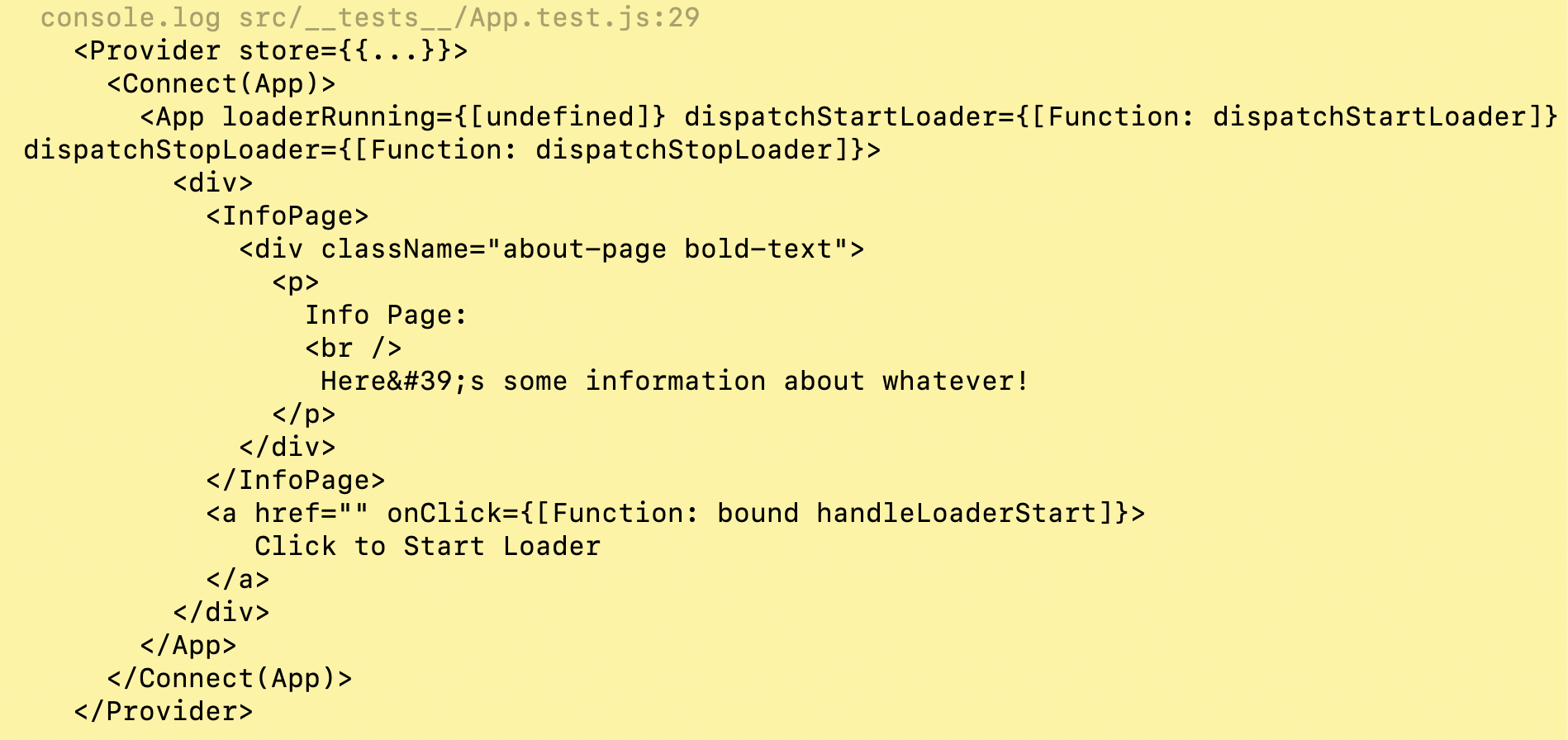

To see where <App> actually is in our mounted wrapper, we can get a visualization printed to our terminal by adding this line after mounting the wrapper: console.log(wrapper.debug()). Here’s the visualization:

Side note: Using wrapper.debug() in conjunction with console.log is hugely helpful when trying to get a sense of what is going on with your wrapper.

You can see that our wrapper object has <App> buried below with its dispatching props methods, #dispatchStartLoader and #dispatchStopLoader. I still don’t quite understand why, but if App.test.js remains as-is, trying to isolate <App> with Enzyme’s #find method (wrapper.find(App)) doesn’t help us. It will only work if we try to #find on a component that is not connected to the Redux store, in this particular instance. So here’s what we can do:

- (i) In

App.js, still export a version of<App>connected to the Redux store (or, more technically, keep exporting a version of<App>within a Redux-connected wrapper). So line 61 ofApp.jsstays the same as above:

export default connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(App)

- (ii) To export a version of

<App>that is not connected to the Redux store, we add another export where we begin the<App>class. So line 10 ofApp.jschanges to become:

export class App extends Component

- (iii) Now we have two exports coming out of

App.js. How do we import them both inApp.test.js? Like this:

import ConnectedApp, { App } from '../App'

<ConnectedApp> expects to be nestled in a <Provider> with a Redux store (or mock store). Meanwhile, unconnected <App> can be isolated with Enzyme’s #find and gives us access to its props, like #dispatchStartLoader and #dispatchStopLoader.

Here’s how we can sew these lessons all together in App.test.js:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

import React from 'react'

import { Provider } from 'react-redux'

import { expect } from 'chai'

import configureMockStore from 'redux-mock-store'

import Enzyme, { shallow, mount } from 'enzyme'

import Adapter from 'enzyme-adapter-react-16'

Enzyme.configure({ adapter: new Adapter() })

import ConnectedApp, { App } from '../App'

import { startLoader, stopLoader } from '../actionCreators'

const mockStore = configureMockStore()

const mockState = {}

describe("<App />", function() {

describe("<App />'s Dispatching Props:", function() {

let store = mockStore(mockState)

let wrapper

beforeEach(function() {

wrapper = mount(

<Provider store={store}>

<ConnectedApp />

</ Provider>

)

})

afterEach(function() {

store.clearActions()

})

describe("#this.props.dispatchStartLoader", function() {

it("dispatches the #startLoader action creator to the Redux store", function() {

const expectedActions = [ startLoader() ]

wrapper.find(App).instance().props.dispatchStartLoader()

expect(store.getActions()).to.deep.equal(expectedActions)

})

})

describe("#this.props.dispatchStopLoader", function() {

it("dispatches the #stopLoader action creator to the Redux store", function() {

const expectedActions = [ stopLoader() ]

wrapper.find(App).instance().props.dispatchStopLoader()

expect(store.getActions()).to.deep.equal(expectedActions)

})

})

})

})

A few important things to note:

- Line 13: Note that we are not testing any changes to the state through these tests, just whether actions were dispatched (via the action creators). That’s why we don’t need to mock any meaningful state, and

mockStateon line 13 can be an empty object ({}). - Line 23: This is where we pass the

redux-mock-storeto<Provider>so we can fully render<ConnectedApp>with Enzyme’s#mount - Line 30: If you are testing actions or action creators in isolated tests but are passing the same mock store to each test, make sure to clear the actions after each test. with

#clearActions(). - Lines 35 and 43: Why are the action creators called by

expectedActionsinside an array? Because#getActionsfromredux-mock-storereturns an array of actions that are dispatched to the store. So if we want to compare our action creators to what#getActions, the former need to be inside an array. - Lines 36 & 44: To get at

<App>’s props (and later, we’ll see, its prototype methods), we need to call Enzyme’s#instancemethod on after we#findit.

Part 2: How can we test that the prototype methods #handleLoaderStart and #handleLoaderStop call #this.props.dispatchStartLoader and #this.props.dispatchStopLoader (respectively)?

Here’s what I learned:

-

These tests are a lot easier to set up than the ones above. We can rely on Enzyme’s

#shallowmethod exclusively, and we do not need a<Provider>, store, or mock store. -

The key to testing which props the prototype methods call is setting the props to equal a ‘spy’ function that will tell you whether the prop function was called. For spying, I used Sinon. After installing it with npm, we can import it into

App.test.js:import sinon from 'sinon'. We set up the spying props before each test on lines 12-15 below. -

If the prototype method calls

event.preventDefault(), it’s not so hard to test whether this is called: set up a mock event object, with a preventDefault key whose value is a spy function. See line 18 below. If you don’t pass a mock event to your prototype method, your tests will throw an error. -

To get access to, and call, the component’s protoype function after

#shallowrendering, usewrapper.instance(). We can also usewrapper.instance().props()to get access to our spies. See, for example, the test code in lines 29-30 below.

Here’s how we can sew these lesson together into additional tests for App.test.js:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

// App.test.js (continued)

import sinon from 'sinon'

describe("<App />'s prototype methods:", function() {

let wrapper

let eventSpy

beforeEach(function() {

const props = {

dispatchStartLoader: sinon.spy(),

dispatchStopLoader: sinon.spy()

}

wrapper = shallow(<App {...props} />)

eventSpy = {preventDefault: sinon.spy()}

})

describe("#handleLoaderStart", function() {

it("calls #preventDefault() on the event", function() {

wrapper.instance().handleLoaderStart(eventSpy)

expect(eventSpy.preventDefault.calledOnce).to.be.true

})

it("calls #this.props.dispatchStartLoader", function() {

wrapper.instance().handleLoaderStart(eventSpy)

expect(wrapper.instance().props.dispatchStartLoader.calledOnce).to.be.true

})

})

describe("#handleLoaderStop", function() {

it("calls #preventDefault() on the event", function() {

wrapper.instance().handleLoaderStop(eventSpy)

expect(eventSpy.preventDefault.calledOnce).to.be.true

})

it("calls #this.props.dispatchStopLoader", function() {

wrapper.instance().handleLoaderStop(eventSpy)

expect(wrapper.instance().props.dispatchStopLoader.calledOnce).to.be.true

})

})

})

All tests pass! Phew. Of course, the tests above do represent everything we may want to test. We’d still need tests proving, for example, that clicking the links calls the relevant prototype methods, and that the action creators called actually update the state as intended. But by proving that <App>’s props dispatch action creators to the store, and that the prototype methods call these props, the tests are on their way to providing coverage that calling the prototype methods in <App> has the desired impact on the state and application as a whole.

I hope seeing this simple example will help generate ideas if you’re looking for how to get running with some tests. The complete code of the snippets above can be found here. Thanks for stopping by!